|

"Discount 200 mg suprax amex, bacteria 5 letters". F. Owen, M.B. B.CH. B.A.O., M.B.B.Ch., Ph.D. Co-Director, Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin

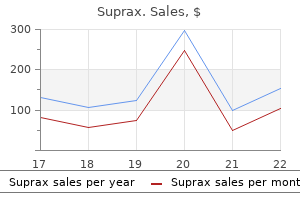

Studies reporting on the relationship of lithium treatment and suicide in patients with bipolar disorder and other major affective disorders have consistently found much lower rates of suicide and suicide attempts during lithium maintenance treatment than without it (562 antibiotics stomach ache purchase 100mg suprax overnight delivery, 563 antimicrobial ipad cover purchase 200 mg suprax fast delivery, 565 antibiotic wipes purchase suprax 200 mg otc, 789) virus usa suprax 100mg discount. These studies included 67 treatment arms or conditions (42 with and 25 without lithium treatment). The total number of patients was 16,221 (corrected for appearance of some subjects in both treatment conditions), and treatment lasted an average of 3. Meta-analysis yielded an overall estimated rate for all suicidal acts (including suicide attempts) from all identified studies of 3. Moreover, the finding of lower rates of suicide and suicide attempts was consistently seen in all 25 sets of observations except one, an early study with a small sample size and relatively short time of exposure to lithium treatment in which no suicidal acts were observed with or without lithium treatment (566). The apparent sparing of risk of suicide and suicide attempts was very similar in patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and in those with other recurrent major affective disorders, although patients with unipolar depressive disorder were evaluated separately in only two relatively small studies involving a total of 121 patients that found a reduction in risk of suicidal acts from 1. Despite these striking reductions in risk, it is also important to note that lithium maintenance treatment does not provide complete protection against suicide. In contrast, the rate of suicide attempts during lithium treatment was very close to the estimated risk for the general population, and the total pooled rate of all suicidal acts with lithium treatment, remarkably, was 33% lower than the estimated general population risk. This striking finding may be plausible in that much of the risk of suicidal behavior in the general population represents untreated affective illness and because suicide attempts are far more common than deaths by suicide. In addition, these observations may suggest a relatively greater effect of lithium treatment on suicide attempts than on suicide, although the variability in relationship to general population risks may also reflect variance in the samples available for the analysis of rates of suicide and suicide attempts. These studies have several notable limitations, including a potential lack of control over random assignment and retention of subjects in some treatment trials, inclusion of some patients with probably unrepresentatively high pretreatment suicide risk, and the presence in several trials of potential effects of treatment discontinuation (565), which can contribute to an excess of early recurrence of affective illness (315, 791, 793, 794), with sharply increased suicide risk (315, 700). However, there was no evidence that the time at risk influenced the annualized computed rate of suicide or suicide attempts. Finding a reduction of suicide risk during lithium treatment also might involve biased self-selection, since patients who remain in any form of maintenance treatment for many months are more likely to be treatment adherent and conceivably also less likely to become suicidal. However, it is not feasible to evaluate any long-term treatment in nonadherent patients. Moreover, several of the reported studies involved either the same persons observed with and without lithium treatment or random assignment to treatment options, minimizing the effects of self-selection bias. Results of these studies were consistent with the overall findings of marked reductions of risk of suicidal behaviors during lithium treatment (565). If lithium is indeed effective in preventing suicide in broadly defined recurrent major affective syndromes, as it appears to be, it seems likely that this effect operates through reduction of Assessment and Treatment of Patients With Suicidal Behaviors 133 Copyright 2010, American Psychiatric Association. An additional nonspecific but potentially important benefit of lithium treatment may arise from the supportive, long-term therapeutic relationships associated with the typically structured and relatively closely medically monitored maintenance treatment of patients with recurrent major mood disorders who are being treated with lithium. Reports from a long-term collaborative German study that involved random assignment of patients with bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder to 2 years of treatment with either lithium or carbamazepine found no suicidal acts with lithium but substantial remaining risk with carbamazepine (592, 597). Approximately 27% of the person-years of exposure were to lithium alone, 22% were to carbamazepine or divalproex alone, and 47% had no exposure to any of the three medications. After adjustment for potential confounds, including age, gender, health plan, year of diagnosis, physical illness comorbidity, and use of other psychotropic medications, the authors found that the risk of suicide was 2. For suicide attempts, the risk during divalproex or carbamazepine treatment was 1. Thus, in patients treated for bipolar disorder, risk for suicide attempts and for suicide was significantly lower during lithium treatment than during treatment with carbamazepine or divalproex. No studies have addressed the risks of suicide attempts or suicide during treatment with other proposed mood-stabilizing agents. Given the widespread and growing use of divalproex, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, topiramate, and other anticonvulsants, often instead of lithium, it is extremely important to include measures of mortality risk and suicidal behavior in long-term studies of the effectiveness of these and other potential treatments for bipolar disorder. Such information may eventually allow an approximate ranking of the effectiveness of specific agents against the risk of suicidal behavior. However, it is not known whether or to what extent they may have beneficial effects in limiting suicide risk in psychotic patients. Some first-generation antipsychotic agents may also have beneficial actions in major affective disorders.

The difference in behavior of building materials with respect to frost damage is due in part to their mechanical properties as bacteria 5th grade generic 100mg suprax, other conditions being equal antimicrobial hand wash discount 200mg suprax visa, stronger materials are obviously more resistant antibiotic ointment for sinus infection buy 100 mg suprax mastercard, but the most important factor is actually the pore size distribution virus plushies generic 200mg suprax with visa. The main cause of frost damage is the fact that crystals in general, and ice crystals in particular, grow easily in the large pores when the conditions for crystallization are reached, while inside capillaries the molecules of the liquid are so strongly attracted to the solid walls that it is difficult to form the seed of a crystal, tearing them out of their position. In large pores a thicker layer of water molecules would keep some of them attached in a relatively weak way so that they are more easily shifted to a new position in a crystal nucleus. If the number of large pores is great and that of capillary pores small, at some point the water reserve is exhausted and the growth of ice crystals stops before they fill the large pores. In this situation no stress arises; the material is now completely dry and the ice crystals are located in the large pores only. A growing crystal, after filling the available space in a large pore, keeps attracting water by capillarity in the gap between its edges and the wall and so exerts a pressure on it. It must be noted, therefore, that the stress caused by the freezing of water inside a porous system is not basically due to the volume increase that is observed when liquid water is transformed into ice; in fact, substances that do not increase in volume upon solidification also can cause damage to porous materials when the temperature drops below their melting point. When frost occurs, if an ice crystal is growing inside a material near its surface, the pressure it exerts is equivalent to a tensile stress acting on a thin layer of brittle material and is very likely to cause damage. This may happen in sedimentary stones when water accumulates at defective joints between layers. As in the case of frost, the growth of crystals may take place only inside the large pores, while the capillary ones store the liquid and feed it to the growing crystals. Therefore, also in this case, a material with abundant capillary pores and a scarcity of large ones is more likely to undergo damage. A supersaturated solution would thus be created inside the pores; its crystallization may then be triggered by some random event and would take place very rapidly throughout the material, its velocity adding more power to the disruptive effect. If crystallization takes place on the surface of the material, it follows its normal route and is not likely to cause stresses and damage; the visible salt crystals form an efflorescence. The internal growth of crystals, which is the most damaging process, is termed a subefflorescence. Actually, both processes frequently take place in the structure of historic buildings and archaeological ruins, the prevalence of one process over the other being determined mainly by the environmental conditions around it. In stratified sedimentary stones, water is transmitted mostly through the layers that are richer in capillary pores; where these layers appear on the surface, crystallization occurs. Wind action accelerates evaporation and sets up the subefflorescence process that results in the formation of small cavities; further damage is then added by local whirlwinds that blast the inner surfaces of the cavities with stone debris. The final result may well be a cavity large enough to threaten the stability of the structure above while nearby surfaces are still well preserved. Actually, the study of salt crystallization damage was one of the factors that led to understanding the importance of compatibility between the materials used in conservation and the original ones. In the treatment of deep corrosion of porous materials caused by salts, the filling material should be at least as rich in capillary pores as the adjoining original; it is even desirable that the future decay (which is unavoidable unless water circulation in the pores is controlled) should first affect the filling, which should sacrifice itself to preserve the original material. The disruptive effect of crystallization is also influenced by the form and size of the crystals, and this in turn is determined not only by pore size distribution and weather conditions but also by the presence of extraneous substances, which may interfere with the growth of the crystals. It was recently proved in a research project that a crystallization inhibitor sharply reduces the damage caused by sodium chloride crystallization by favoring the formation of very small crystals and inhibiting their adhesion to other crystals or to the pore walls. Small separate crystals are apparently unable to cause damage in that particular case. It appears that different substances act as inhibitors for different classes of salts;. Unfortunately, the encouraging results obtained in the laboratory have not been reproduced in actual field conditions up to the present time, a likely cause of problems being the difficulty of achieving a satisfactory distribution of the inhibitor in pores that are already full of water and salts. Under this heading we list calcareous stones (white marble, travertine, limestone, calcarenite, calcareous tuff) and lime-based mortars (renderings, stuccoes). The chemical reactions involved are, in theory, the ones shown in the scheme in figure 3. As a consequence, oxalates do not migrate under the action of water but remain where they have been formed, and the result is the development of surface layers, patinas, which are of interest in the conservation of historic architecture. Oxalate patinas are frequently found on the surface of ancient stones (roman, medieval but occasionally also on more recent ones) exposed to urban atmospheres. Their color may vary from yellow to pink to red and brown; on northfacing surfaces and in polluted atmosphere, they may even be black. Calcium oxalate is the dominant component (20% to 60%) but not the only one, and frequently the patina appears under the microscope to be constituted of several layers.

Overcoming delayed germination in the seed of plants valuable for erosion control and wildlife utilization [thesis] medication for recurrent uti generic 200 mg suprax overnight delivery. A guide to selection and propagation of some native woody species for land rehabilitation in British Columbia virus affecting kids 100mg suprax visa. The genus Physocarpus includes about 6 species of deciduous infection 1 game buy cheap suprax 200 mg on-line, spiraealike shrubs with exfoliating bark antibiotics zedd buy 100mg suprax with mastercard, alternate and lobed leaves resembling Ribes, and small white to pinkish flowers in corymbs. The common name, ninebark, probably refers to the use of the plant in a number of medicinal cures (Stokes 1981) or the numerous layers of bark that peel off (Strausbaugh and Core 1978). Five species are native to North America, and one is introduced from Asia (table 1). Although the genus is not wide-spread, certain species may be locally abundant because of root sprouting. Atlantic ninebark and common ninebark, 2 varieties of opulifolius - the specific epithet refers to Viburnum opulus, an introduced species from Europe (Stokes 1981)-are the most common species in the eastern United States and are found along streams, riverbanks, and moist hillsides. Of the western species, dwarf ninebark is found mostly in rocky canyons and low-elevation forests of California and grows to 1 m in height; mountain ninebark is found from foothill forests to mountain tops of the central and southern Rocky Mountains and grows to 1 m in height; mallow ninebark is found in rocky canyons and low-elevation open forests throughout the Rocky Mountains and grows to 2 m; and Pacific ninebark is found in moist to wet lowlands or foothills mostly west of the Cascade Range and grows to 3 m. They are used primarily as ornamentals in landscaping or for watershed protection. Most of the species have been cultivated in the United States for nearly 100 years (table 1). In the wild, mallow ninebark sprouts prolifically from the root crown after spring and fall fires (Lea and Morgan 1993). Although the genus is reported to be remarkably free from insects and diseases (Everett 1981; Gill and Pogge 1974), at least 17 flower-eating, 63 leaf-and-stem-eating, and 4 seed-eating insects have been identified on common ninebark, including the flower-specialist mirids Plagiognathus punctatipes Knight and Psallus physocarpi Henry and seed-specialist torymids Megastigmus gahani Milliron and M. Flowers are complete, regular, and clustered together in terminal corymbs consisting of a few in mountain and mallow ninebarks, 3 to 6 in dwarf ninebark, and many in Pacific and common ninebarks. Flowers of Pacific ninebark appear in April through June, those of mountain ninebark appear in May through June, and those of mallow and common ninebarks in June. The fruits are small, firm-walled, inflated follicles (figure 1); the generic name Physocarpus is derived from the Greek physa ("bladder" or "bellows") and karpos ("fruit"), referring to the bladder-shaped follicles (Stokes 1981). Common name dwarf ninebark Amur ninebark Pacific ninebark mallow ninebark Occurrence California to Nevada Manchuria & Korea Alaska, British Columbia, Montana, south to California British Columbia to Montana, south to Oregon, Utah, & Wyoming First cultivated - 1856 1827 1897 P mountain ninebark South Dakota to Texas, Arizona, Nevada Maine to Minnesota, S to Tennessee & Florida Quebec to North Dakota, S to Colorado, Arkansas, & 1889 common ninebark 1687 Atlantic ninebark Missouri 1908 number 3 to 5 in Amur, Pacific, common, and Atlantic ninebarks. When mature, the follicles tend to be brown, reddish, or coppery in color, glabrous in common ninebark and sometimes Pacific ninebark, otherwise stellate-pubescent. Each follicle may contain several seeds, which are shiny and pyriform (figures 1 and 2). Seed ripening is indeterminate and does not always result in good fill (Link 1993). Ripe fruits can be picked from the shrubs or shaken onto dropcloths, dried either naturally or with artificial heat, and then threshed with a hammermill, and cleaned. Seeds of common and Atlantic ninebark are extracted by dry maceration followed by handscreening to remove debris and follicle fragments (Yoder 1995). The seeds are orthodox and may be stored for at least 5 years when cool and dry (Link 1993). Mallow ninebark seeds may be planted in the fall or planted in the spring after 30 days of prechilling (Link 1993). Seeds of common ninebark and Atlantic ninebarks are sown in raised beds either in the fall or in the spring after 60 days of prechilling (Yoder 1995). Seeds are mixed one part seeds to three parts (by volume) dry, sifted sawdust to provide bulk and facilitate even distribution; sown at a depth of about 3 mm (1/8 in); and mulched with a layer of sawdust about 6 mm (1/4 in) thick (Yoder 1995). The ninebarks are easily propagated by softwood cuttings planted under mist, or hardwood cuttings planted in the field (Everett 1981; Dirr and Heuser 1987).

The olive fruit consists of carpel antibiotics sinus infection yeast infection generic suprax 200 mg on line, and the wall of the ovary has both fleshy and dry portions virus 68 in children buy 100mg suprax mastercard. The flesh (mesocarp) is the tissue eaten antibiotic resistance assay buy 100 mg suprax amex, and the pit (endocarp) encloses the seed antibiotics for dogs skin purchase suprax 200 mg amex. Fruit shape and size and pit size and surface morphology vary greatly among cultivars. The mature seed (figure 1) is covered with a thin coat that covers the starch-filled endosperm (figure 2). These wild types are known to have existed in the region of Syria about 6,000 years ago (Zohary and Spiegal-Roy 1975). From the eastern Mediterranean, olive trees were spread west throughout the Mediterranean area and into Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and France. The Franciscan padres carried olive and other fruits from San Blas, Mexico, into California. Sent by Jose de Galvez, Father Junipero Serra established Mission San Diego de Acala in 1769. Though oil production began there in the next decade, the first mention of oil was written in the records of Mission San Diego de Alcala in 1803 as described by Father Lasuen. By the 1900s, California olive oil production had met the competition from imported olive oil and American vegetable oil and, in an effort to survive, the canning olive industry was born. During the 20th century, the California canning olive occupied a strong market position in America, with olive oil as a salvage industry. Currently, a renewed emphasis in health benefits of monosaturated olive oil has lead to a resurgence of olive oil production in California. The olive tree has been used widely for shade around homes and as a street tree in cities. A smaller collection exits at the United States Germplasm Repository at Winters, California. Floral initiation occurs by ally mature in September or October (ready for the California black-ripe or green-ripe process), and physiologi- November (Pinney and Polito 1990), after which, flower cally mature in January or February. Unlike deciduous fruits with a short ally mature by October, and if harvested and stratified at that induction-to-initiation cycle, induction in olive may occur as early as July (about 6 weeks after full bloom), but initiation time it will achieve maximum germination (Lagarda and is not easily seen until 8 months later in February. When the fruit is physiologically mature by microscopic and histochemical techniques reveal evidence January, seed germination is greatly reduced. The origin of olive is lost in prewritten ing all the flower parts starts in March. In experiments with the cultivars grown in California, optimum flowering occurred when the temperature fluctuated daily between 15. In addition to winter chilling, inflorescence formation requires leaves on the fruiting shoots. The occasional occurrence of hot, dry winds during the blooming period has been associated with reduced fruit set. Prolonged, abnormally cold weather during April and May, when the olive flower buds should be developing rapidly, can have a detrimental effect on subsequent flowering, pollination, and fruit set. Such weather occurred in California in the spring of 1967, delaying bloom by several weeks and leading to flower abnormalities and a crop of only 14,000 tons, the lightest in modern California history. At full bloom, flowers are delicately poised for pollination, when some 500,000 flowers are present in a mature tree; a commercial crop of 7 metric tons/ha (3 tons/ac) or more can be achieved when 1 or 2% of these flowers remain as developing fruit. By 14 days after full bloom, most of the flowers destined to abscise have done so. By that time, about 494,000 flowers have abscised from a tree that started with 500,000 flowers.

|

|